Falsification

a meditation on adopted and transgender people's identity rights

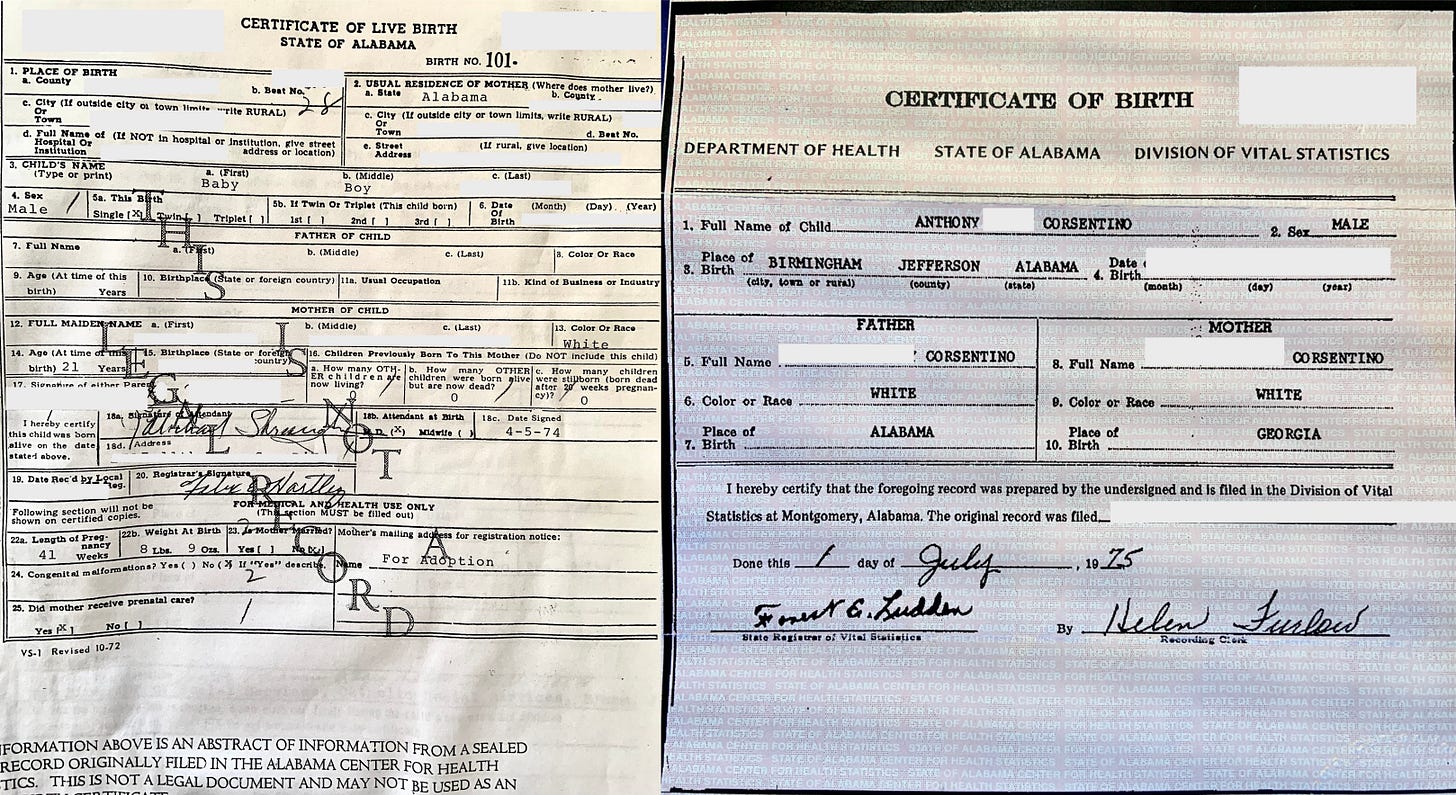

There is a hanging file folder in my desk drawer that holds both my birth certificates.

I file them together because together they embody the upside-down pairing of two contrasts: the one that records the actual facts is legally null, and the one that ordains fictitious facts is legally binding.

Adoptees find dark humor in the the absurdity of amending a birth certificate: “I need a fake birth certificate to get my Real ID.” My amended Certificate of Birth lists people who had no relation whatever to the event of my birth. For most of my life I didn’t see any humor in this. Now I invoke the cliché “Kafkaesque.”

I’ve heard it argued that merely calling the document a certificate of birth, or certificate of “live birth,” does not entail any particular relationship, biological or otherwise, to the parents listed on the document. The point of the document, in this reasoning, is to certify the person’s identity and legal parentage. This is the claim often made by adoptive parents in defense of the practice: that unless their names appear on their child’s birth certificate, the legal protections and prerogatives of parenthood would not exist.

This is a curiously narrow view of the landscape of possibilities. There is nothing so sacrosanct about the birth certificate that the legal entitlements attaching to parenthood can only be secured through it, rather than by other means. Against the idea that the birth certificate is merely a statement of legal parentage (despite the presence of “live birth”-relevant facts like birth weight), I adduce the example of late-discovery adoptees, fooled (as I call it) for much of their lives about their status as adoptees, and about their actual parentage. Because the birth certificate makes no reference to an adoptee’s adoption (a fact relevant to legal parentage if any is), it smoothly enables adoptive parents with a passing physical resemblance to their children to conceal the truth of their adoption.

And so I maintain that the adoptee’s amended birth certificate is a legally sanctioned lie, and that the practice of sealing the original record and issuing a falsified version violates the right to one’s identity.

And not only do I maintain that the practice of sealing the original record violates the adoptee’s identity rights. I also maintain—as I emphasized in my first post to this newsletter, “Fourteen Propositions”—that the common belief that adoption engenders a conflict between the adoptee’s right to their identity and the birth parent’s entitlement to confidentiality (or right to privacy) is a conceptual confusion.

That is because privacy is the keeping of facts about oneself to oneself; so the right to privacy is the right to limit or withhold others’ access to facts about oneself. But the parentage of a person—of any person, adopted or otherwise—is obviously not a fact solely about that person’s parents. It is a fact about them both. Both parent and child claim ownership of it. Neither is entitled to block the other’s access to it. And so the concept of privacy fails to apply here.

(An aside. In a fuller philosophical treatment of this argument I would need to address the concept of “facts about oneself,” because all sorts of facts can be trivially described as such, and do not fall within the argument’s scope. For example, and to anticipate: it might be a “fact about me” that I work with a particular colleague whose gender identity diverges from their gender expression; it does not follow that I have a right to know this “fact about me,” i.e., to know that this colleague’s gender identity so diverges. Clearly, I have no such right. In my argument I am making use of the intuitive idea that if I have a right to any “facts about me” at all, I surely have a right to the identity-defining fact that I am the offspring of particular people.)

I believe people overlook the idea of an adoptee’s entitlement to knowledge of their parentage because we are unaccustomed to thinking of infants and children as possessing any but the most basic rights, such as the right not to be murdered or abused. We don’t think of babies and very young children as “knowers,” and we fail—routinely and constantly fail—to consider that the adopted baby before us today will grow into an adolescent and adult. Part of the predicament of being an adoptee is forever being thought of in terms appropriate for children, in a state of almost total dependence upon others.

Having dwelt on questions of identity and its legal obfuscation, I come to a question that pricks my conscience whenever I say that to amend a birth certificate is to falsify it. For I believe that it is a basic right of human beings to embrace and express a gender identity that does not align with the sex assigned to them at birth. And there are legal avenues in every state except Tennessee for transgender people to petition to amend their birth certificates to the sex that aligns with their gender identity. Most of these states require proof of gender-affirming surgery. But not my state, Massachusetts:

Neither do California, New York, Oregon, Vermont, Washington State, and a few others. They have no surgical requirement, but they impose a less restrictive requirement of medically guided transition. That proof of medically guided transition is required at all reflects the birth certificate’s status as a vital record: often, procedures for changing sex markers on other official documents, such as driver’s licenses, are less restrictive still.

Nonetheless, a birth certificate amended to record the sex that aligns with a trans person’s identity is no longer a record of the “facts of the birth,” insofar as the sex assigned at birth is such a fact. Here again, as with the idea of a “fact about me” (see the parenthetical aside above), there are complexities in the concept of a “fact about” someone that require a deeper examination.

And all of this “pricks my conscience,” as I said earlier, because I believe trans people have a right to their identities no less than I as an adoptee have a right to mine. A trans person who realizes that their true gender identity diverges from their assigned sex and socially affirmed/imposed gender identity is discovering the truth about themselves, just as in tracking down the identity of my biological parents I discovered the truth about myself. So when a trans person’s petition to change the sex recorded on their birth certificate is approved, does it become falsified?

The first salient difference between the two cases is that trans people willingly amend their own records; adoptees have their records amended for them. The next important difference, flowing from the first, is that trans people are at no point debarred from access to the revision history of their own documents, simply because it is they who are revising them, hence creating that history. But might we not still say that trans people are willingly and autonomously falsifying their birth records?

They are not falsifying their gender identity. Nor are they falsifying their sex, insofar as the entire point of medical transition (surgical or otherwise) is to bring their sex into alignment with their true gender identity. If the amended version falsifies anything, it “falsifies” the historical sex they were assigned at the time of the certificate’s original issuance.

And so the result is a “falsification” autonomously performed by the very person to whom it applies, who for that reason is not “deceived” by the change.

But in fact there’s even more to distinguish this case from that of amending the adoptee’s birth certificate. Because in most states, a birth certificate amended to update the sex field is marked “amended.” Rules vary by state. In Massachusetts, the marker might not indicate which fields have been changed. In Alabama, the amended certificate explicitly notes that the sex field has been changed. Without examining the overall wisdom and fairness of such policies, I will only note that they reflect a conception of the birth certificate as a “vital record” of “biological” attributes and relationships.

Because a transgender person retains control of the process of amending their own birth certificate to align it with their true gender identity (which is not to say doing so is as easy as it ought to be), and because at no point are they denied access to the document at any stage, pre- or post-revision, I think that such amendments, which are so limited in scope and deceive and harm no one, scarcely deserve to be called falsifications.

And so to my transgender friends I say: In demanding recognition of our rights, our struggles share this broad similarity. We are demanding that our rights to our identities be taken seriously—in social opinion and in law.

Very helpful and well-considered, as always, Tony. Thank you.

Kudos for clarifying the important differences between replacing an adopted person’s original birth certificate and a trans person choosing to replace and actually correct their own OBC.

An adoptee’s OBC is sealed and altered, without the knowlwdge or consent of the person whose BC is changed, the adoptee.

What hit me hard in seeing your OBC was how truly callous it is. “THIS IS NOT A LEGAL DOCUMENT,” slashes down across the OBC. Well, it WAS a legal document before they sealed it. Then they *replaced* it with a forged fake adoptive birth certificate. And if that was stamped on my OBC? I would wonder, did that mean I was an illegal newborn baby? Some people who were adopted don’t even learn that they were adopted until late in their life. This causes the adoptee intense pain, confusion, anger and an identity crisis the likes of which Freud never imagined.

And why is the infant named “Baby Boy?” Was your mother even allowed to name her own baby? Or did the name she chose for you, her child, get dropped in favor of the commodity name?

Then the last space at the bottom of the OBC for, “Mother’s Mailing Address for Registration Notice,” where they just typed in, “For Adoption.” To me, that is heartbreaking. And the truth: Plenary adoption erases who we were — with the supposed goal (in most cases during the Baby Scoop Era) of erasing the stain of being born a bastard.

Sorry folks, but it didn’t work. For myself, my parents never hid from me that I was adopted. I found it fascinating that I grew in some other Mommy’s tummy. But soon I knew to the marrow of my bones there must have been something wrong with me, for my own mother to give their own baby, me, away to complete strangers.

We have the human right to the truth of our origins, including our unaltered, unamended OBC, along with knowledge of and information about our original birth family, family medical history, and any other of OUR OWN information contained within our adoption case file, court records, etc.

There’s an underlying constant wistful grief connected to being adopted, though sometimes I put it on the back burner because it’s just too confusing and painful. It’s hard to grow up as a tulip in a bed of daisies, never quite fitting in, rarely feeling any certainty about who we really are.

Thank you, Tony, for clearly and logically speaking on issues which seem muddy so often in the way people do talk about adoption.