About a month ago, Representative Marjorie Taylor Greene (R-GA) entered into the politics of kinship language when at a hearing of the House Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Pandemic, she questioned the credentials of Randi Weingarten, president of the American Federation of Teachers, who had advised the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on school closures and other public-safety efforts.

At the hearing, Weingarten described herself as a “mother by marriage” (having married a woman with children from a prior marriage), thereby failing Greene’s test of motherhood, which requires being a biological parent.

This prompted outrage from Democrats. Representative Maxwell Alejandro Frost (D-FL) offered perhaps the most pointed rebuke among the variety to appear on Twitter:

Another, Rep. Jimmy Gomez (D-CA), had this to say:

Another account, not of an elected official but one that offers hot takes from a generally liberal/progressive perspective, responded to Greene’s attack on Weingarten by claiming that far from being a necessary condition for motherhood, a biological connection to the children one is raising is perhaps “the least of it.”

To disclose: I took issue with this claim, and the account promptly clapped back with a hostile quote-tweet. Others countered that I had misunderstood the point of these responses to Greene, which was not about adoptees’ relation to their adoptive parents at all, but merely about calling out Greene’s homophobia.

It is, of course, beneath contempt to suggest that a woman in a same-sex marriage who helps raise biologically unrelated children does not deserve the label “parent”—whether because she is biologically unrelated or because she is queer. But in choosing to affirm who truly deserves the label—and, further, by asserting the insignificance of the genealogical link—these responses to Greene effectively partner with her in centering the parents and speaking over the offspring, ignoring their authority (and ambivalence) over the use of kinship language.

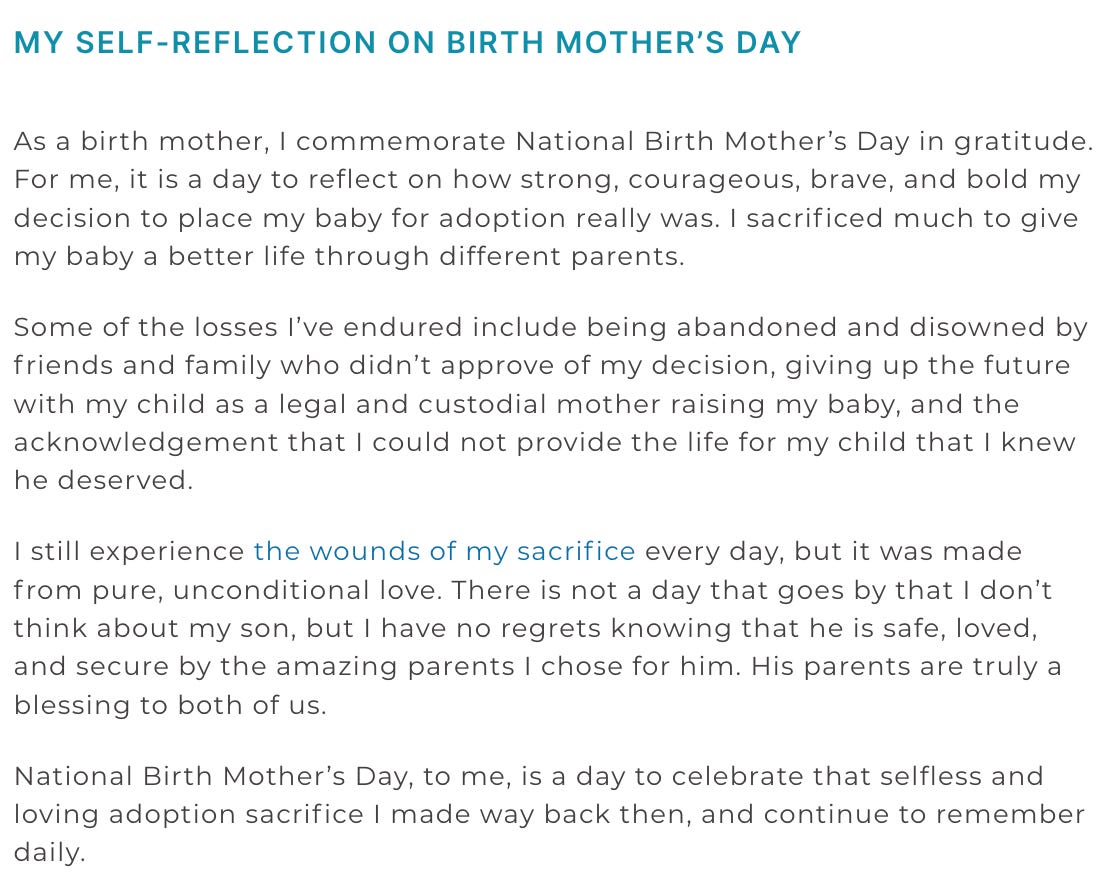

In my previous post, #notallmothers, I wrote about how celebrations of parenthood foreground the labor of parenting, implicitly delegitimizing the status of parents legally severed from their children. Consider Birth Mother’s Day, designated as the Saturday before Mother’s Day, which looks on its face to honor that status, but only by sharply distinguishing it from custodial motherhood. The idea is not to give birth mothers an additional holiday, but to give them an alternative to the one that excludes them.

In linguistics jargon, “mother” and “birth mother” form an unmarked/marked pair. Grammatically, the marked form is derived from the unmarked: it’s an adjectival modification of the unmarked, basic form. Semantically, the marked/unmarked distinction denotes a contrast between the basic or “standard” idea and an idea that is defined by its special divergence from the basic idea. “Mother” denotes the basic idea of motherhood; “birth mother” denotes the special idea of legally severed motherhood.

What is essential to the basic idea of motherhood? For Greene’s critics, it is the labor of mothering. The basic, unmarked form of motherhood is that of being a woman who performs the care labor (or is legally charged with the responsibility of care labor) of raising a child. On this understanding of motherhood, adoptive motherhood is not a contrast to motherhood (unmarked); it constitutes a kind of motherhood (unmarked). Whereas birth motherhood isn’t a kind of motherhood (unmarked) at all; it stands in contrast to motherhood (unmarked).

There is a Birth Mother’s Day, but no Adoptive Mother’s Day. We tacitly understand that Mother’s Day celebrates adoptive mothers, because the basic idea of motherhood is to be a woman who mothers. On the surface, it seems ironic that adoption agencies pay the greatest lip service to Birth Mother’s Day:

But the irony vanishes when we see that Birth Mother’s Day honors the “strong, courageous, brave, and bold” decision to place a baby for adoption. In a sense, Birth Mother’s Day also honors a form of doing, instead of a form of being. It honors the act of relinquishing—of unmothering. Birth Mother’s Day is designed to reinforce the inclusion of adoptive mothers in the basic idea of motherhood-as-caregiver. To be a birth mother is to be an unmother.

Greene’s concept of motherhood is obscure. Does she regard the childbearer-offspring connection as essential? Or is she primarily concerned to demonize queer motherhood? It is generally unproductive to try to rationally reconstruct hatred. Leaving Greene aside, what can we say about her detractors? They demonstrate how deeply rooted is the mothering conception of motherhood. Our cultural idea of motherhood is tailor-made for adoptive parenting; it is mother/birth mother, not mother/adoptive mother, that marks the genuine opposition.

I refuse to bestow “mother” as an exclusive honorific upon either of the claimants to that word—these two women with utterly different ways of being in my life, each present only when the other was absent. The mother/birth mother opposition encodes a clear prejudice against women who have lost their children to adoption, and it feels like a theft of language from people like me, who insist on the sole right to describe our family trees, cleaved at the root.

For me (an Australian adoptee) I find the most challenging thing about all things "mothers' day/s" is that it is still all about them. As babies and children we had no agency in decisions that impacted us for life. Once I became a mother myself any enjoyment of "that day" with my own children took decades to overcome the anxiety of managing any expectations and the 'other' mothers' emotional needs. It is tiring. I decided not to celebrate or acknowledge the public construction of the day at all and put my own needs first now on this one.

Another profound and beautiful essay--thank you, Tony.