Beautiful Man

I picture my relationship to my childhood memories as something like the view, from an airplane at 30,000 feet, of cloud cover far below. Most of the landscape is hidden behind a gray blankness, save what I can glimpse through the occasional hole. Last night I caught such a glimpse when I suddenly remembered that Greg Louganis, decorated Olympic diver and household name in 1980s USA, was adopted as an infant, and that my adoptive parents extolled him as a role model for me. I Googled his name and found a 2017 article on People.com, from which I learned the story of his reunion with his biological father and, in time, with more of his original family.

This set off a rush of memories I hadn’t revisited in forty years, and with them, a tumble of startlingly intense emotions. I realized I had resented Greg Louganis as a child. I remembered that I felt mild, malicious satisfaction at the news that he had sustained a concussion at the 1988 Seoul Games. As a child and then adolescent I did not theorize these feelings, and I now know why. To theorize them—to understand that my resentment was grounded not in Greg Louganis the person but in my parents’ tokenizing of him as what adoptees can achieve—I would have needed to be able to theorize my own resentment of my parents. And to do that, I would have needed to be able to theorize my adoption in terms that separated myself, and my questions and needs as an adoptee, from my parents, and their motives and needs as adopters. Like other people adopted in my time and circumstances, I had nothing in my emotional and social lifeworld to nurture that ability, and plenty to suppress it.

Greg Louganis met his father, Fouvale Lutu, in 1984, during a promotional event in Honolulu. I was ten years old when it happened. Since Louganis appears not to have spoken publicly about it before the past decade, my parents were not in a position to decide whether to incorporate the idea of the adoptee-in-reunion into their image of Greg Louganis as the adoptee-who-made-good. Yet I feel the urge to call this another instance of the erasure of everything that does not support the dominant conception of adoption as child welfare through family creation—the excision and orphaning of the story, of the very idea, of finding and reclaiming one’s roots from that happy conception.

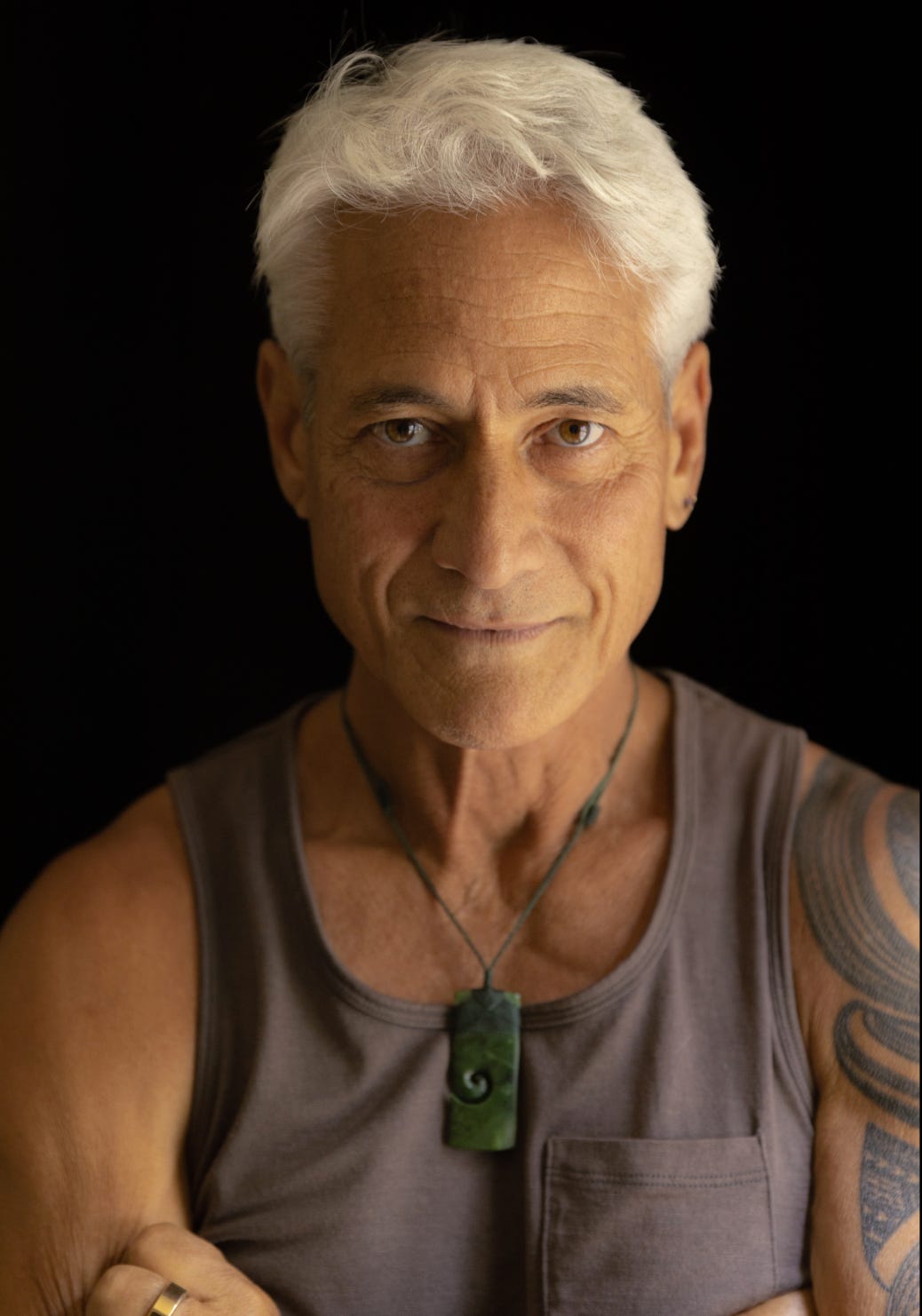

All I know about Greg Louganis’s reunion story derives from one brief news piece published in 2017. At the time, he had confirmed the identity of his birth mother through DNA databases, but he had yet to meet her. I don’t know whether he has met her since. But what I have is this extraordinary portrait.

It’s a powerful image of a beautiful man. What strikes me most is how, while retaining the Greek name bestowed by his adoptive parents, he claims his Pacific Islands heritage in how he presents himself—in the pendant and, especially, in the magnificent tattoo on his left shoulder and arm, which, given the available photographic evidence, he appears to have gotten within the past five years.

I travel across two timelines as I study this portrait. I think of the person I am now, having reunited with my birth mother’s family; having reconciled with my adoptive father; having spoken, sparingly and warily, with my biological father. Thinking of Greg Louganis sends my imagination back to the ten-year-old boy I was, telling him So much lies in store; you will find what’s being hidden; it’s good to be a searcher; Greg Louganis is a searcher too, you just don’t know it yet. And I imagine telling the 24-year-old Greg Louganis I wish you could share this with the world; you can’t imagine how many people need to know that reunions can happen; it’s going to change you too, you just don’t know how yet.

Erasure, as I have used the term here, is a cultural project requiring many interconnecting parts: laws, institutions, ideas. Denial of citizenship to intercountry adoptees is one manifestation of it. Also, adopting children out of their communities; punitive, draconian terminations of parental rights through our systems of family policing; sealing of birth records. More broadly still: ideas of adoption as child rescue, and the presumption of adoptee gratitude, function to enmesh everyone in the project of erasure. Against such a polymorphous force, resistance takes correspondingly many forms. Greg Louganis’s his willingness to talk about his reunion, and his reassertion of his ancestral identity through inscribing and adorning his body, are potent acts of anti-erasure, no matter how personal their meaning for him.

I caught a glimpse of something through the clouds, and at first it seemed ugly, but it turned out to be beautiful. This is what de-fogging can be like.

Greg, accompanied with his husband had a reunion with his birth mother in 2017. I don't cis het people understand why we gay/queer adoptees don't search. It's about rejection. Not only do we have a loss of identity but then we get the message that our sexuality is wrong by our parents and society. It's why I kept quiet about it even now in the adoptee community many of us aren't supported. I am glad he found both parents and his family.

Tony, this was beautifully written. It greatly impacted me.