On Narrating What Happened

It is a potent and radical act for an adoptee to tell their adoption story factually and neutrally

It’s a familiar plot conceit: They’ve taken you from your family, your town, possibly even your country. They’ve given you a new life. They’ve erased or sunk in a bureaucrat’s file your former identity, and issued you a new one. There are twists on the conceit:

You know they did this, and you know or remember something about your former life, and you had consented to it.

You know they did this, but you don’t remember your former life, although you had consented.

You don’t remember even that they did this, although you had consented.

This is the stuff of thrillers and spy novels. And then there are the versions where these things happened and you do or don’t remember that they did, except you did not consent. You are an unwilling pawn in someone else’s scheme. That’s the stuff of dystopian novels. And of adoption.

Non-adoptees tend to react in a curious way when an adoptee narrates a life story that involves, if only implicitly, erasing and replacing their original identity: with indifference. Erasure doesn’t generally appear to strike kept people as a loss, a calamity, at all. Separation is another thing: kept people understand that one generally relinquishes a child only in circumstances of crisis. The typical response to separation—the social counterpart to the legal fact of severance—is to find a silver lining: to say that it was “brave” or “deeply loving” or, incredibly, “unselfish” (!) for a parent to give their own child to another family—part of the idea of the adoptee as “blessed.”

There is romance in the language of adoption. Adoptees speak of their birth parents as having “given them up,” a phrasing that connotes sacrifice, selflessness, and agency. For the birth parent to have done such a brave and (for them) devastating thing for the benefit of their own flesh and blood, is surely a blessing to the adoptee. Part of a double blessing, since the adoptee has a new family that gives nurturance and protection, which the first could not.

It is possible that children, untrained in the socially approved rhetorical treatment of adoptees, see a different picture if the story is told in a different, “impolite” way.

Seonju Oh Bickley decided to narrate the facts, “being as neutral about it as possible.” It isn’t my place to speculate on how much of Seonju’s adoption story fits the dystopian template we considered earlier. My own birth and adoption story, narrated in a neutral and matter-of-fact style, includes constraint, desperation, geographical displacement, the kindness of strangers, and the legal engineering, without my awareness or comprehension, of a new identity and network of family relationships. Seonju’s story involves a displacement that is deeper and broader than mine: a radically different geographic, racial, cultural, and linguistic context from her original home. When we consider that pregnant people in crisis are so often unfree, deprived of viable options, we should not wonder at how a child, not disciplined in the polite way of talking about adoption, would call it kidnapping. Often enough, both historically and today, it is literally that. Traffickers did, and do, trick parents into relinquishing their rights, or outright steal children. Notoriously, Georgia Tann (1891-1950), perhaps the preeminent innovator in creating the system of plenary adoption as we know it in the United States, was a relentlessly energetic kidnapper and child trafficker.

I think there is power in an adoptee’s plainly, neutrally narrating their story. By “plainly, neutrally” I mean in a manner that avoid both moralizing and imputing motives, attitudes, and feelings to the parties of the adoption triad. Compare:

Polite Version (that I heard). Your birth parents were very young when your birth mother became pregnant with you. They knew they couldn’t give you the life you deserved, and they loved you so much they decided it was best to give you up for adoption. It wasn’t an easy decision, but they acted in your best interests. The adoption agency placed you with two people who wanted very much to have a child, and they took you and made you part of their family.

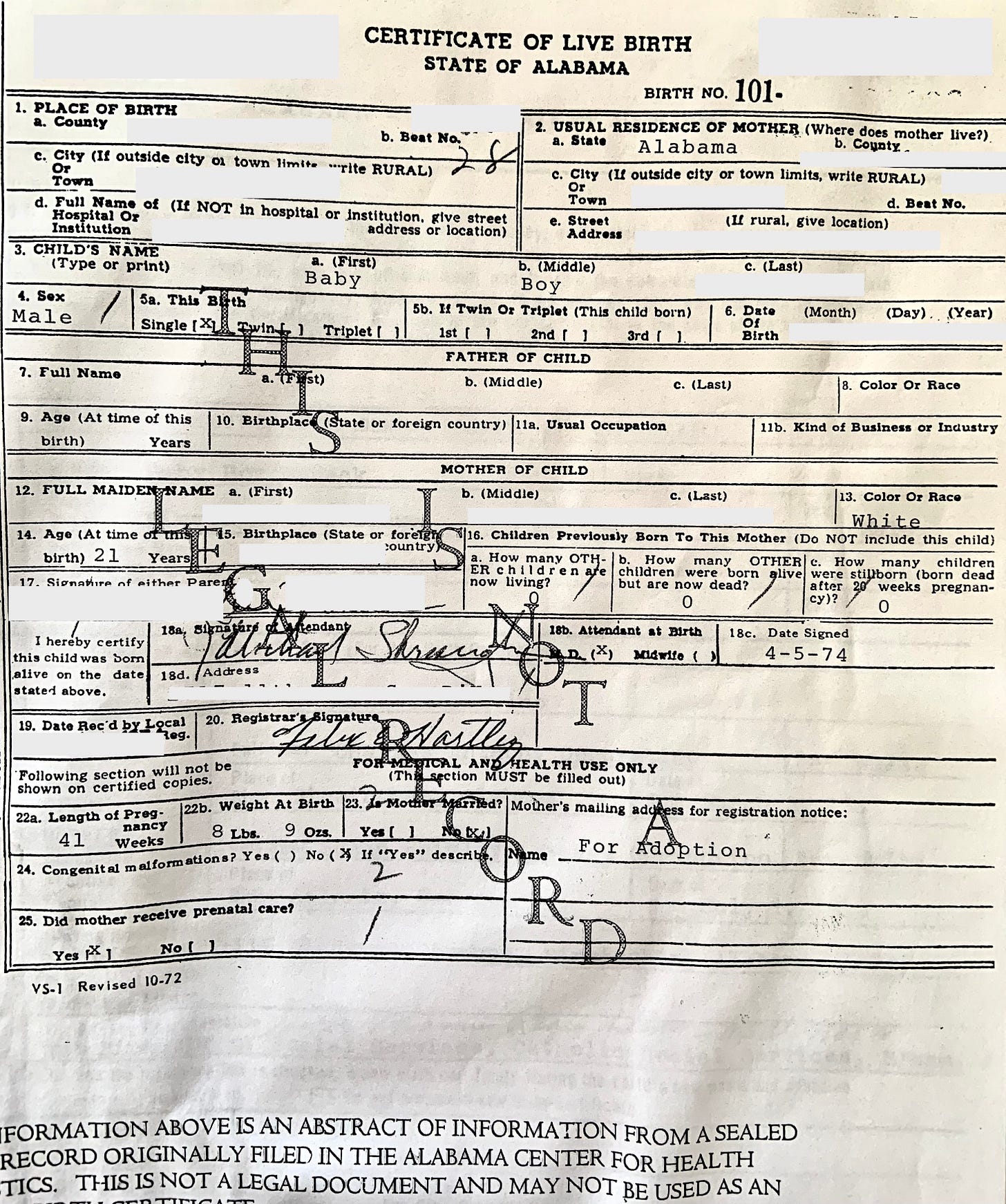

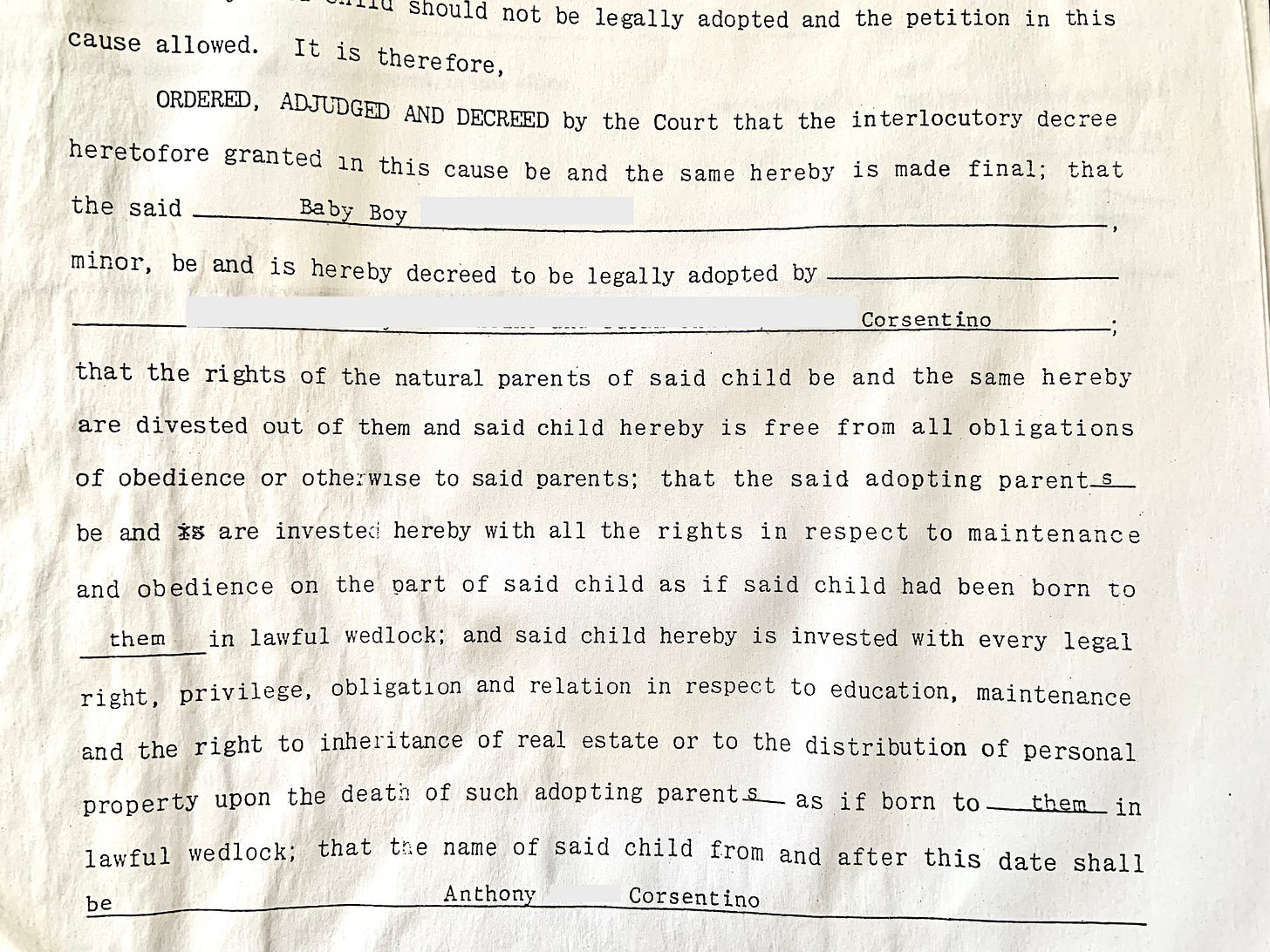

Neutral Version (that I tell). X became pregnant. After [description of X’s economic, social, and familial circumstances, including the relevant actions of the biological father and of X’s family], X elected to carry the pregnancy to term. X was informed that her only option was to remove herself, temporarily, from her community and family, and to carry out her pregnancy in the company of people unknown to her. [Description of the locale and setting, and circumstances of my birth.] After [interval of time, possibly zero] of caring for me, X terminated her parental rights and passed me into the care of an adoption agency. After [interval of time], the agency granted an unrelated married couple, identities unknown to X and vice versa, custodial responsibility for me. After [interval of time, in fact 14 months after my birth], the couple was granted a formal decree of adoption, giving them legal parental rights over me. My birth certificate was declared an invalid legal record, and I was issued an altered birth certificate, formally indistinguishable from any other birth certificate issued in that state, which identified and certified the married couple as my birth parents. The original document was placed under seal, openable only by court order.

Above is my original birth certificate: not a legal record.

Above is the decree of my adoption, finalized fourteen months after I was born. There is little I know about where I was, and with whom, during those months.

The neutral version gains power the more facts the teller can include. But also powerful are the facts about what the teller doesn’t know, is blocked from knowing—that (e.g.) I don’t know of my whereabouts or treatment for the first several months of my life. Relinquishment is almost always a desperate response to a crisis. Severance is drastic: a permanent solution to what often proves to be a temporary problem. That it prevails as the solution illustrates where the power does, and does not, lie among the members of the adoption triad. Seonju’s child’s response to her neutral telling of her story shows this. The line between “giving” a child and having it taken, when the facts are better known, can get blurred.

Since a dispassionate narration of the facts foregrounds the parent, who relinquished their own child for adoption, it counters the tendency to demote that parent to a secondary status, as a mere “birth” or “biological” parent.1 It opens up questions that the polite versions of our adoption stories suppress: Could the child have been placed with members of its extended family? Why must the child have been expelled from its community, its country, its culture of origin? Why don’t parent and child know who each other are, or what is happening in their lives? Did the parent actually desire lifelong severance? Do parents who relinquish generally desire this, or should we interrogate what lies behind the polite assumption that they do?

Reimagining the terms of our adoption stories is a step in our efforts to be publicly visible as a distinct group with distinct interests. Severance, to repeat, is draconian: it radically reconfigures family relationships. Given the unpredictability of time and change, it can often look like an unforgiving, even brutal way to treat a person in crisis. When the story is the traditional one of agency, choice, and boundless love for a child, on all sides, no one questions why. When we strip the story to its factual bones, we can begin to ask: Why do we flesh it out as we do? And whom does that serve?

I discussed this in my comments on Proposition 1 of my “Fourteen Propositions About Adoption.”

Thank you for your clear analysis and compassionate voice

This is so good, Tony. I think Substack is the new blogosphere! You're quickly coming to be a very important voice here.